Planning screening programmes

In addition to the effectiveness of the screening test, a number of other elements should be considered when planning a screening programme.

The approach

Screening programmes use one of two approaches:

- Opportunistic - screening is done as part of routine care when patients visit their doctors

- Proactive - the population targeted for screening are actively identified and invited to participate in the screening programme.

The disease

Opportunities for effective early intervention created by screening programmes depend on the natural history of disease.

The test

See earlier section about evaluating the performance of screening tests.

Cost

The cost-effectiveness of a screening programme can be difficult to assess. There are a number of costs to consider:

- The cost of the test itself

- Costs of reading and interpreting the test

- Cost of diagnostic follow-up tests

- Cost of the programme management and data processing

- Cost of treating more cases that are identified due to the screening programme

- Cost of treating more advanced disease in the absence of a screening programme

- Opportunity costs for the health service and the individual.

Quality

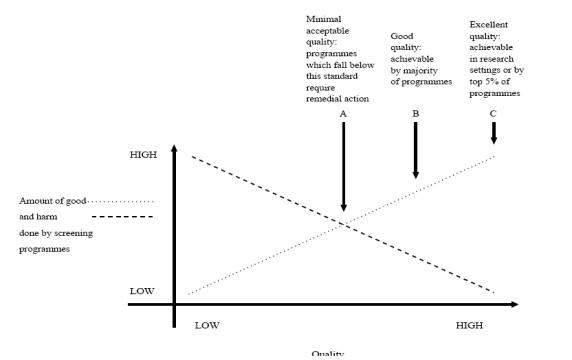

- Randomised controlled trials provide robust evidence for the effectiveness of a screening test, but the results may be difficult to reproduce in the real-world service setting.

- Variation in quality of service delivery may change the balance of harm and benefit of a screening programme.

- The final appraisal of whether or not to introduce a screening programme should ask whether a sufficient level of quality can be achieved at a reasonable cost, even if it does not reproduce the effectiveness achieved in a research setting.

- This balance between harm/benefit and quality of service delivery is summarised in the figure below.

Source: National Screening Committee (2000)

The role of the UK National Screening Committee

In the UK, the National Screening Committee (UK NSC) (https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/uk-national-screening-committee-uk-nsc) advises ministers and the NHS in the four UK countries about all aspects of screening and supports the implementation of screening programmes. Conditions are reviewed against specific evidence review criteria according to the UK NSC evidence review process in order to establish the screening programme’s viability, effectiveness and appropriateness. The UK NSC does this by:

- Reviewing evidence about the effectiveness of screening

- Commissioning research on screening

- Advising on the introduction of new screening programmes

- Reviewing the continued delivery of screening programmes

- Assessing the quality of screening programme delivery.

Quality assurance

The screening programmes must participate in external Quality Assurance and have internal quality assurance processes that ensure failsafe is integral to the programme and incident management occurs in line with failsafe document/map of medicine and national guidelines for incident management (https://www.gov.uk/guidance/nhs-population-screening-quality-assurance).

Operational steps to implementing screening programmes

In addition to playing a major role in the quality of screening programmes, the UK NSC is charged with ensuring effective implementation of screening programmes.

- Identification of target population

- Invite target population

- Inform target population of screening programme and gain consent

- Administer screening test

- Interpret result of the test

- Communicate results of the test

- Follow-up testing/surveillance (as required)

- Treatment (as required)

- Data management systems

- Programme coordination, oversight, and quality assurance

- Ongoing monitoring and evaluation

Evaluating screening programmes

The UK NSC proposes 20 criteria (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/evidence-review-criteria-national-screening-programmes/criteria-for-appraising-the-viability-effectiveness-and-appropriateness-of-a-screening-programme) for appraising the viability, effectiveness and appropriateness of a screening programme. These draw on the Wilson and Jungner criteria and can be summarised as:

The condition

- Is there good evidence (from systematic reviews or randomised controlled trials) showing that early intervention in the disease improves outcomes?

The test

- Is it safe?

- Will it work in our population and healthcare system?

The intervention/treatment

- Is there an effective treatment that can be used following early identification of the disease?

The programme

- What are the benefits and harms of the screening programme?

- Is it cost effective?

Implementation criteria

- Are there appropriate facilities, staffing, expertise, training for treating the condition?

- Is there an agreed plan for managing and monitoring the quality of the screening programme?

Epidemiological artefact may increase the perceived benefits of the screening programme due to lead time and length time bias.

Lead Time Bias:

When screening appears to increase survival time simply because the disease is detected earlier. Once this is taken into account, there may be little or no effectiveness of the screening test (i.e. improvement in survival time). For example, screening using prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test identifies prostate cancer in a patient at age 50 years but despite treatment he dies at 60 years. Without screening he might have been diagnosed at 57 years old and died at 60 years. Thus, it falsely appears that survival is 7 years longer with screening, even though his survival is the same without screening.

Length Time Bias:

An overestimation of survival because long-duration cases are more likely to be detected and treated than short-duration cases. For example, annual PSA screening is more likely to detect a slow-growing tumour of the prostate, which is also more likely to be detected while still at a treatable stage.

Reference materials

- Criteria for appraising the viability, effectiveness and appropriateness of a screening programme. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/evidence-review-criteria-national-screening-programmes/criteria-for-appraising-the-viability-effectiveness-and-appropriateness-of-a-screening-programme

- Second Report of the UK National Screening Committee. (2000). London: National Screening Committee, UK

© Dr Murad Ruf and Dr Oliver Morgan 2008, Dr Kelly Mackenzie 2017