Health care evaluation is the critical assessment, through rigorous processes, of an aspect of healthcare to assess whether it fulfils its objectives. Aspects of healthcare which can be assessed include:

- Effectiveness – the benefits of healthcare measured by improvements in health

- Efficiency – relates the cost of healthcare to the outputs or benefits obtained

- Acceptability – the social, psychological and ethical acceptability regarding the way people are treated in relation to healthcare

- Equity - the fair distribution of healthcare amongst individuals or groups

Healthcare evaluation can be carried out during a healthcare intervention, so that findings of the evaluation inform the ongoing programme (known as formative evaluation) or can be carried out at the end of a programme (known as summative evaluation).

Evaluation can be undertaken prospectively or retrospectively. Evaluating on a prospective basis has the advantage of ensuring that data collection can be adequately planned and hence be specific to the question posed (as opposed to retrospective data dredging for proxy indicators) as well as being more likely to be complete. Prospective evaluation processes can be built in as an intrinsic part of a service or project (usually ensuring that systems are designed to support the ongoing process of review).

There are several eponymous frameworks for undertaking healthcare evaluation. These are set out in detail in the Healthcare Evaluation frameworks section of this website and different frameworks are best used for evaluating differing aspects of healthcare as set out above. The steps involved in designing an evaluation are described below.

Steps in designing an evaluation

Firstly it is important to give thought to the purpose of the evaluation, audience for the results, and potential impact of the findings. This can help guide which dimensions are to be evaluated – inputs, process, outputs, outcomes, efficiency etc. Which of these components will give context to, go toward answering the question of interest and be useful to the key audience of the evaluation?

Objectives for the evaluation itself should be set (remember SMART) –

S - specific – effectiveness/efficiency/acceptability/equity

M - measurable

A - achievable – are objectives achievable

R - realistic (can objectives realistically be achieved within available resources?)

T - time- when do you want to achieve objectives by?

Having identified what the evaluation is attempting to achieve, the following 3 steps should be considered:

1. What study design should be used?

When considering study design, several factors must be taken into account:

- How will the population / service being evaluated be defined?

- Will the approach be quantitative / qualitative / mixed? (Qualitative evaluation can help answer the ‘why’ questions which can complement quantitative evaluation for instance in explaining the context of the intervention). Level of data collection and analysis - will it be possible to collect what is needed or is it possible to access routinely collected data (e.g. Hospital Episode Statistics if this data is appropriate to answer the questions being asked)?

- The design should seek to eliminate bias and confounding as far as possible – is it possible to have a comparator group?

- The strengths and weaknesses of each approach should be weighed up when finalising a design and the implication on the interpretation of the findings noted.

Study designs include:

a) Randomised methods

- Through the random allocation of an intervention, confounders are equally distributed. Randomised controlled trials can be expensive to undertake rigorously and are not always practical in the service setting. This is usually carried out prospectively.

- Development of matched control methods has been used to retrospectively undertake a high quality evaluation. A guide to undertaking evaluations of complex health and care inteventions using this method can be found here: http://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/sites/files/nuffield/publication/evaluation_report_final_0.pdf

- ‘Zelen’s design’ offers an alternative method incorporating randomisation to evaluate an intervention in a healthcare setting.

b) Non randomised methods

- Cohort studies - involve the non-random allocation of an intervention, can be retrospective or prospective, but adjustment must be made for confounders

- Case-control studies – investigate rare outcomes, participants are defined on the basis of outcome rather than healthcare. There is a need to match controls however the control group selection itself is a major form of bias.

c) Ecological studies

- cheap and quick, cruder and less sensitive than individual level studies, can be useful for studying the impact of health policy

d) Descriptive studies

- used to generate hypotheses, help understand complexities of a situation and gain insight into processes e.g. case series.

e) Health technology assessment

- examines what technology can best deliver benefits to a particular patient or population group. It assesses the cost-effectiveness of treatments against current or next best treatments. See economic evaluation section of this website for more details.

f) Qualitative studies

- Methods are covered in section 1d of this textbook.

- Researchers-in-residence are an innovative method used in evaluation whereby the researcher becomes a member of the operational team and brings a focus to optimising effectiveness of the intervention or programme rather than assessing effectiveness.

2. What measures should be used?

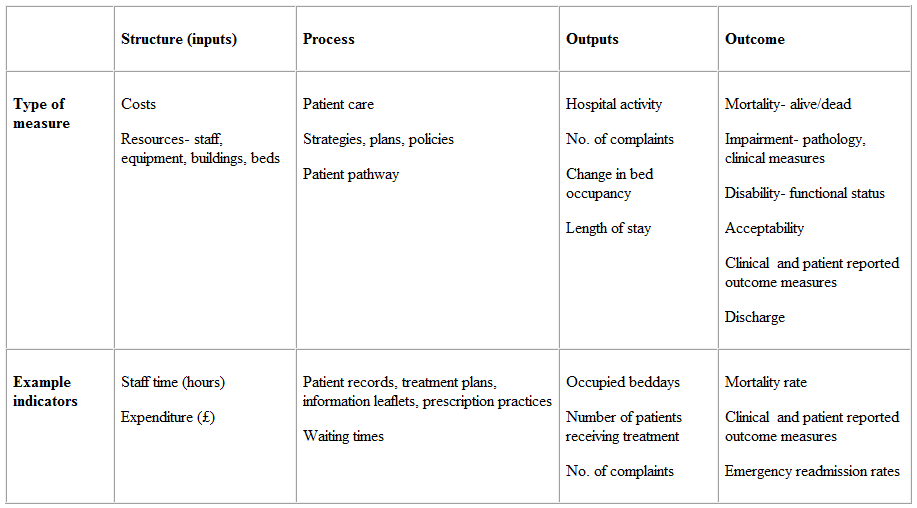

The choice of measure will depend on the study design or indeed evaluation framework used as well as the objectives of the evaluation. For example, the Donabedian approach considers a programme or intervention in terms of inputs, process, outputs and outcomes.

- Inputs - (also known as structure) describes what has gone into an intervention to make it happen e.g. people, time, money

- Process - describes how it has happened e.g. strategy development, a patient pathway

- Outputs - describe what the intervention or programme has produced e.g. throughput of patients

- Outcomes - describes the actual benefits or disbenefits of that intervention or programme.

The table below gives some further examples of measures that can be used for each aspect of the evaluation. Such an evaluation could measure process against outcomes, inputs versus outputs or any combination.

3. How and when to collect data?

The choice of qualitative versus quantitative data collection will influence the timing of such collection, as will the choice of the evaluation being carried out prospectively or retrospectively. The amount of data that needs to be collected will also impact on timing, and sample-size calculations at the beginning of the evaluation will be an important part of planning.

For qualitative studies, the sample must be big enough that enlargement is unlikely to yield additional insights e.g. undertaking another interview with a member of staff is unlikely to identify any new themes. Most qualitative approaches, in real life, would ensure that all relevant staff groups were sampled.

For quantitative studies the following must be considered (using statistical software packages such as Stata):

- the size of the treatment effect that would be of clinical/social/public health significance

- the required power of the study

- acceptable level of statistical significance

- variability between individuals in the outcome measure of interest

If the evaluation is of a longitudinal design, the follow up time is important to consider, although in some instances may be dictated by availability of data. There may also be measures which are typically reported over defined lengths of time such as readmission rates which are often measured at 7 days and 30 days.

Trends in health services evaluation

Evaluation from the patient perspective has increasingly become an established part of working in the health service. Assessment of service user opinion can include results from surveys, external assessment (such as NHS patient experience surveys led by the CQC) as well as outcomes reported by patients themselves (patient reported outcome measures) which from April 2009 are a mandatory part of commissioners’ service contracts with provider organisations and are currently collected for four clinical procedures; hip replacements, knee replacements, groin hernia and varicose veins procedures.

© Rosalind Blackwood 2009, Claire Currie 2016