Introduction

The structure of health services in the UK after the second world war reflected disparate origins and artificial divisions between different elements, which had persisted for many years. The three main strands, state owned (nationalised) hospitals, a national network of general practitioners and community and domiciliary health services, were financed centrally but managed separately. Throughout the history of the NHS, this initial division of functions between separate statutory organisations created problems in the provision of comprehensive and co-ordinated services.nA report published in 1956 (Guillebaud Report), expressed early concern about many issues, which is still familiar.

These included:

- Changing trends in health and illness.

- The importance of prevention of illness.

- The needs for GPs and hospitals to work closely together.

- The need to make adequate provision for the care of old people Whether the NHS would in practice be able to meet every demand justifiable on medical grounds.

The health and social care system continues to face significant challenges of the future including:

Rising expectations: the public wanting more from their public services, to match the choice, customer service and personalisation they get elsewhere, and wanting services to be more local and convenient too.

The demographic challenge: with an ageing population and increasing numbers of people with long-term conditions including serious disabilities, increasing demand.

The revolution in medical technology: transforming the ability of the NHS to prevent, cure and manage diseases, alleviate suffering and extend life expectancy, but this creates new costs

Continuing variations in the safety and quality of care: needing an NHS that delivers care of the highest possible safety and quality in every place and at every time, in particular through honest and open information about the outcomes achieved by providers.

Health Service Planning

‘Health services planning’ is a common term. It reflects the growing interest in the topic in the 21st century. The term can mean different things to different people, i.e. a notion of social engineering applied to healthcare or the design of a health

facility.

‘Health services planning’ has been described as:

A process that appraises the overall health needs of a geographic area or population and determines how these needs can be met in the most effective manner through the allocation of existing and anticipated future resources (Thomas 2003:3).

Ultimately, all planning comes down to identifying the needs of the target population and then determining the best means for meeting those needs. However, within the health sector there is uniqueness about the planning process that doesn’t occur within industry. This includes:

- Emotional dimensions - fluctuations in demand and the fact that health service providers are often dealing with life-and-death situations.

- Complex relationships - the healthcare industry is also made of many separate entities operating in a virtually uncoordinated manner and often at cross-purposes and characterised by a variety of different customers.

- Financial characteristics – different from other industries whereby the end-user may not make the consumption decision or pay for the service provided

- Diversity of functions – different entities perform different functions and single entities, e.g. a hospital, performs multiple functions simultaneously. The functions can range from, providing for the healthcare needs of a population to providing a community service and others seeing their role as humanitarian or seeing themselves as contributing to the safety of the public.

Health care needs vary according to the age structure and health profile in a population. The likelihood of people seeking care is determined by a range of social and cultural factors and will impact upon demand for care. The likelihood of people receiving care is determined by policy decisions and will impact upon the volume of activity in the health system.

Planning activities and terms

There are many planning terms, which need to be understood in order to clarify the relationship between these planning approaches. A summary of these terms is given below:

|

Terms |

Activity |

|

Economic/development planning |

National level activity aimed at steering the economic or development policies, primarily though public expenditure or fiscal policies |

|

Strategic plan |

Document outlining the direction an organisation is intending to follow, with broad guidance as to the implications for services or action |

|

Business plan |

Strategic plans prepared by business organisations setting out their direction, and usually providing income and expenditure projections |

|

Regulatory planning |

Activities of State planning bodies that set planning guidelines for private sector activities |

|

Service/programme planning |

Planning focusing on the services to be provided. Used to contrast with capital planning (see below) |

|

Capital planning |

Planning focusing on the capital developments of an organisation such as its building programme |

|

Project planning |

Planning focusing on discrete time-limited activities |

|

Human resource/manpower planning |

Plans focusing on the human resource requirements of an organisation or country |

|

Physical plans |

Plans relating to construction elements |

|

Operational plans |

Activity plans detailing precise timing and mode of implementation |

|

Work plans |

Operational plans referring to the activities of a small unit or of an individual |

(Green 2007.49)

Initiating Health Services Planning

There are many reasons for initiating a health services planning process, which can emerge from, the community, an organisation or the interest of a particular group or individual. However, any healthcare services plan is going to reflect the influence of the political, social and economic considerations that are within that particular healthcare environment. Health service planning can therefore be undertaken on the basis of change arising from:

- healthcare reforms which changed accountability and decision making within the NHS

- health care needs which can change over time according to the age structure and health profile in a population; e.g. the increasing numbers of older people mean a concomitant increase in disability and illness, in particular those of dementia, musculoskeletal and cardiovascular diseases, and sensory impairment. Health and social systems need to address the treatment and care of the increasing numbers of people with these problems.

- technological advances which continuously challenge the health service. Technology and medical advances are major drivers of health expenditure and have significant potential to improve the outcomes and the efficiency of the health service.

- evidence-base programmes setting quality standards and specifying services, e.g. NICE recommendations and qulity standards.

The challenge for the planner is to balance the objective, technical dimension of planning with the realities of the context within which the planning is taking place.

Planning approaches

There are various different approaches to health service planning which can range from ‘problem solving’, ‘long-term versus shorter operational plans’ and ‘narrative approaches’ which uses matrices presenting a nested set of objectives set in tabular form. Plans may also be aimed at particular services or institutions or at wider geographical areas.

Within health planning there are two broad types:

- activity planning – is concerned with the maintenance of existing situations and the setting of monitorable implementation timetables.

- allocative planning – is concerned with the possibility of change and the making of decisions on how resources will be used and which activities will be undertaken.

The outcome of planning is conditioned by the behaviour of individuals and groups at all levels in the process. The NHS planning system is an enabling mechanism, which should facilitate a more effective use of the scarce resources available for health care.

Concerns about planning

The history of planning in the health sector is still relatively short and has not always been successful. The dilemma that gives rise to the needs for planning is often the gap between available resources and health needs, leading to the requirement to make choices as to how to use these resources. Plans often fail to be implemented or are implemented but fail to respond adequately to the real needs of the populations. Common examples are the imbalance of resources between preventive care andcurative care, between different social groups, between different regions orgeographical areas, between staff salaries and medical supplies, or between different types of staff such as generalists and specialists. If planning is to be strengthened in the future it is important to understand the reasons for any of these occurrences. A variety of reasons can contribute to poor planning processes and include:

- planning becomes an end in itself, with the real aim, that of effecting change – submerged under the planning process

- technical failure to analyse needs appropriately or to estimate resources accurately

- imposing plans from the centre in a top-down fashion, without the involvement of both the health-care providers and the communities in the decision

- the planning process has been isolated from other decision-making processes such as budgeting or human resource planning

- the failure to consider the inherently political nature of the process.

NHS reforms have encouraged a patient-led NHS that uses available resources as effectively and fairly as possible to promote health, reduce health inequalities and deliver the best and safest possible healthcare.

Planning Mechanisms and Techniques

Joint Strategic Needs Assessment: In England The Local Government and Public

Involvement in Health Act (2007) also specified that local authorities and partners produce a Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA) of the health and wellbeing of the local community. Needs assessment is an essential tool for commissioners to inform service planning and commissioning strategies. The findings of the JSNA should inform a number of local plans.

The stages in preparation of a JSNA will include:

- stakeholder involvement

- engaging with communities

- suggestions on timing and linking with other strategic plans

- development of a core dataset.

Guidance on utilising JSNA to provide insight into local commissioning, publishing and feedback can be found at

The JSNA provides a framework to examine all the factors that impact on health and wellbeing of local communities, including employment, education, housing, and environmental factors. Local authorities and PCTs can build on this core dataset, using clearly defined criteria to select additional, high quality and locally relevant information that provides a clear picture of their area.

Undertaking Health Service Planning

Who is involved?

Planning is concerned with change and the prospect of change inevitably brings opponents and supporters of the proposal. The relationship between planners, policy makers, service-managers, communities and other stakeholders in the planning process is critical to the success of planning. A significant number of health planners are drawn from health professions, e.g. medicine, nursing, and public health, however one of the challenges today is not so much a matter of trying to develop specialist health planners but rather that of exposing a broad range of professionals to the importance and concepts of planning in order that they can participate in the process. A second challenge is to ensure that planning systems are designed and operated so as to provide real (rather than token) input from communities and users in the planning process.

Many techniques are used to assess the importance of stakeholders’ influence including stakeholder analysis (see Theories of strategic planning).

What is involved?

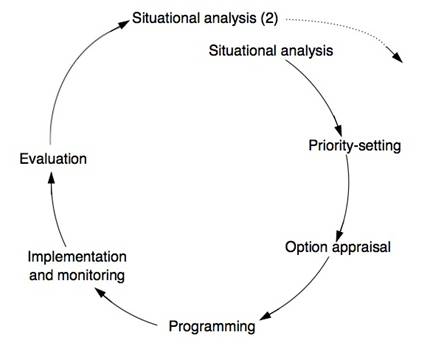

The following diagram represents a cyclical set of activities frequently found during a planning process. It can be described as a planning spiral, with the end point of each cycle forming the start of the next cycle, but at a higher plane.

The Planning Spiral (Green 2007:36)

Each stage is briefly described below with links to examples in the field.

Situational analysis: involves assessing the present situation and

includes:

- current and projected demographic characteristics of the population

- physical and socio-economic characteristics of the area and its infrastructure

- analysis of the policy and political environment including existing health policies

- analysis of the health needs of the population

- services provided by non-health sector as well as health sector, focusing on facilities provided, their function and service gaps together with organisational arrangements

- examination of resources in the provision of services including their current efficiency, effectiveness, equity and quality

The situational analysis needs to cover the whole of the health sector.

Priority-setting: stage ensures that the priorities set are feasible within the social and political climate and within the context of available resources. Clear criteria are therefore required for the selection of priority problems, which reflect the goals, objectives and targets of the organisations involved. In some situations it may be helpful to clarify first what are not priorities (e.g. where local needs are low, where expectations cannot be met or significant achievements have been made and needs are now less pressing.

Option appraisal: stage involves the generation and assessment of the various alternative strategies for achieving the set of objectives and targets. Options may be discarded at this stage due to high resource implications, political or social unacceptability, or technical unfeasibility. The results of this stage will be a list of preferred strategies or combination of approaches which will then form part of the plan.

Programming budgeting: Programme Budgeting (PB) is an appraisal of past resource allocation in specified programmes, with a view to tracking future resource allocation in those same programmes. In addition, Marginal Analysis (MA) is the appraisal of the added benefits and added costs of a proposed investment (or the lost benefits and lower costs of a proposed disinvestment. Together PBMA is a priority-setting framework that helps decision-makers maximise the impact of healthcare resources on the health needs of a local population.

Example: PBMA in eight steps (Brambleby and Fordham):

- Step 1: Choose a set of meaningful programmes with which to work

- Step 2: Identify current activity and expenditure in those programmes

- Step 3: Be creative – consider possibilities for improvements and linkages in pathways and patterns of care within and between programmes

- Step 4: Weigh up extra costs and increased benefits of the improvements that were thought of in Step 3

- Step 5: Consult widely – there may be options, trade-offs and value judgements to explain

- Step 6: Decide on the change and make the decision in public

- Step 7: Effect the change – this is the essence of management – making it happen

- Step 8: Evaluate your progress – check that the anticipated costs, saving and outcomes actually materialised.

To find examples from these steps see (http://www.bandolier.org.uk/painres/download/whatis/pbma.pdf)

Implementation and monitoring: is an essential part of the planning process which involves transforming the broad strategies and programmes into more specific timed and budgeted set of tasks and activities and involves drawing up more operational plans which can then be monitored.

Evaluation: provides the basis for the next situation analysis and is an integral component of the process. Reflection upon whether the process has enhanced joint working, the needs analysis has been sufficiently appropriate and comprehensive and if there are any gaps or areas of concern that need further analysis.

Using the Planning Spiral can brings all aspects of planning into a coherent, unified process.

References

- Department of Health (2002) Delivering the NHS Plan next steps on investment next steps on reform London: Crown

- Department of Health (2008) Joint Strategic Needs Assessment Quality Assurance Toolkit NHS East of England

- Green, A. (2007) An Introduction to health planning for developing health systems Oxford University Press

- Greengross, P.; Grant, G.; Collin. E. (1999) The history and development of the UK National Health Service 1948 – 1999 HSRC

- Ham, C (1999) Improving NHS performance: human behaviour and health policy

British Medical Journal 319(7223): 14990-1492 - Mitton, C. and Donaldson, C. (2004) Priority Setting Toolkit A Guide to the Use of Economics in Healthcare Decision Making London: BMJ Publishing

- Pencheon, D.; Guest, C.; Melzer, D.; and Gray, M.J.A. (2006) Oxford Handbook of Public Health Practice Oxford University Press

- Rathwell, T. (1987) Strategic Planning in the health sector Kent: Croome Helme

- Thomas, R.K. (2003) Health Services Planning New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers

© S Markwell 2009, C Beynon 2017