Principles and Practice of Health Promotion: Health Promotion and Healthy Public Policy

This section covers:

- Collective and individual responsibilities for health, both physical and mental

- Interaction between genetics and the environment (including social, political, economic, physical and personal factors) as determinants of health, including mental health

- Ideological dilemmas and policy assumptions underlying different approaches

- The role of legislative, fiscal and other social policy measures in the promotion of health (see also Health Promotion and Intersectoral Working)

- International initiatives in health promotion

- Opportunities for learning from international experience

- Concepts of deprivation and its effect on health of children and adults

Introduction

This section looks at the development of health promotion and its contribution to public health policy. It considers the contributions of individual behaviour and social, environmental and economic determinants to health. The determinants of health are explained using the 'Policy Rainbow' model, the WHO publication 'The Solid Facts' and the WHO Commission for Social Determinants. The development of the public health movement and the role that health promotion has played in conceptualising this is described, considering the Lalonde 'Health Field concept' and WHO Health for All by the Year 2000. Ideological models of health promotion and the Ottawa Charter are also described in this section.

1.1 Models of determinants of health

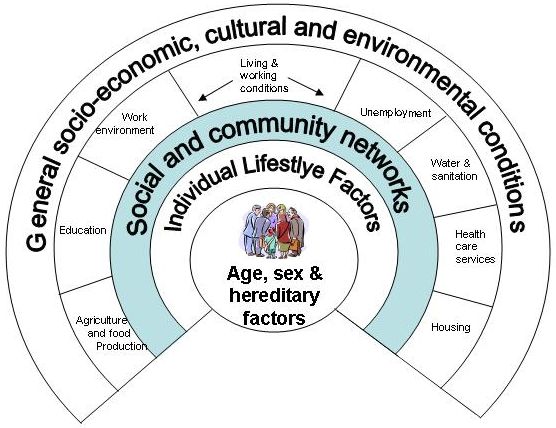

The health and well-being of individuals and populations across all age groups is influenced by a range of factors both within and outside the individual's control. One model, which captures the interrelationships between these factors is the Dahlgren and Whitehead (1991) 'Policy Rainbow', which describes the layers of influence on an individual's potential for health (Fig. 1.1). Whitehead (1995) described these factors as those that are fixed (core non modifiable factors), such as age, sex and genetic and a set of potentially modifiable factors expressed as a series of layers of influence including: personal lifestyle, the physical and social environment and wider socio-economic, cultural and environment conditions.

The Dahlgren and Whitehead model has been useful in providing a framework for raising questions about the size of the contribution of each of the layers to health, the feasibility of changing specific factors and the complementary action that would be required to influence linked factors in other layers. This framework has helped researchers to construct a range of hypotheses about the determinants of health, to explore the relative influence of these determinants on different health outcomes and the interactions between the various determinants. For example in the US the relative impacts that the various domains of health determinants have on early death have been estimated as follows:

-

30% from genetic predispositions

-

15% from social circumstances

-

5% from environmental exposures

-

40% from behavioural patterns

-

10% from shortfalls in medical care

However this might only be applicable to US or another western country with similar socioeconomic, environmental conditions and a similar population. Places with different population structure, under different conditions, will show a very different picture. As an example, in a country where a civil was breaks out, people's health can deteriorate quite rapidly due to the general socio-economic and environmental conditions; because suddenly factors like availability of food, shelter and drinking water will become dominant in determining health as compared with other factors.

Fig. 1.1 A Social Model of Health (Dahlgren & Whitehead, 1991)

In 2003 WHO published an influential document 'The Solid Facts' on the social determinants of health, which reviewed the evidence for causal relationships between social and environmental factors and health, and outlined policy implications (Wilkinson & Marmot, Eds, 2003). They point out that:

'Poor social and economic circumstances affect health throughout life. People further down the social ladder usually run at least twice the risk of serious illness and premature death as those near the top. Nor are the effects confined to the poor: the social gradient in health runs right across society, so that even among middle-class office workers, lower ranking staff suffer much more disease and earlier death than higher ranking staff. Both material and psychosocial causes contribute to these differences and their effects extend to most diseases and causes of death. Disadvantage has many forms and may be absolute or relative. It can include having few family assets, having a poorer education during adolescence, having insecure employment, becoming stuck in a hazardous or dead-end job, living in poor housing, trying to bring up a family in difficult circumstances and living on an inadequate retirement pension. These disadvantages tend to concentrate among the same people, and their effects on health accumulate during life. The longer people live in stressful economic and social circumstances, the greater the physiological wear and tear they suffer, and the less likely they are to enjoy a healthy old age. ' (p10).

The evidence points to the existence of a clear social gradient and nine topic areas which should be addressed in healthy public policy, they are: the lifelong importance of health determinants in early childhood, and the effects of poverty, drugs, working conditions, unemployment, social support, good food and transport policy. However the authors also state that while study of the human genome may lead to advances in the understanding and treatment of specific diseases, 'however important individual genetic susceptibilities to disease may be, the common causes of the ill health that affects populations are environmental: they come and go far more quickly than the slow pace of genetic change because they reflect the changes in the way we live. '

The following table (1.1) summarises the key facts about each area and policy implications, but readers are highly recommended to refer to the whole document.

Table 1.1 extracts from The Solid Facts (Wilkinson & Marmot, 2003)

| Topic and health impact | Policy implications |

|

Stress Stressful circumstances, making people feel worried, anxious and unable to cope, are damaging to health making people susceptible to infections, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart attack, stroke, depression and aggression, and may lead to premature death.

|

Although a medical response to biological changes from stress may be to try to control them with drugs, attention should be focused upstream, on reducing the major causes of chronic stress.

|

| Early Life

A good start in life means supporting mothers and young children: the health impact of early development and education lasts a lifetime. Slow growth and poor emotional support raise the lifetime risk of poor physical health and reduce physical, cognitive and emotional functioning in adulthood. |

Policies for improving health in early life should aim to:

|

| Social Exclusion

Life is short where its quality is poor. By causing hardship and resentment, poverty, social exclusion and discrimination cost lives. Poverty and social exclusion increase the risks of divorce and separation, disability, illness, addiction and social isolation and vice versa, forming vicious cycles that deepen the predicament people face. |

All citizens should be protected by minimum income guarantees, minimum wages legislation and access to services.

|

| Work

Stress in the workplace increases the risk of disease. People who have more control over their work have better health. |

|

| Unemployment

Job security increases health, well-being and job satisfaction. Higher rates of unemployment cause more illness and premature death. |

Employment policy should have three goals: to prevent unemployment and job insecurity; to reduce the hardship suffered by the unemployed; and to restore people to secure jobs. |

| Social Support

Friendship, good social relations and strong supportive networks are known to improve health at home, at work and in the community. |

Reducing social and economic inequalities and reducing social exclusion can lead to greater social cohesiveness and better standards of health.

|

|

Addiction Individuals turn to alcohol, drugs and tobacco and suffer from their use, but use is influenced by the wider social setting. |

Work to deal with problems of both legal and illicit drug use needs not only to support and treat people who have developed addictive patterns of use, but should also aim to address the patterns of social deprivation in which the problems are rooted.

|

| Food

Because global market forces control the food supply, healthy food is a political issue.

|

|

|

Transport Healthy transport means less driving and more walking and cycling, backed up by better public transport. |

|

In 2005 the WHO launched a new initiative, the Commission on Social Determinants (CSDH), to draw the attention of governments, civil society, international organisations and donors to the health effects of social determinants. A key aim of the CSDH is to highlight international and national causes of inequalities and find practical ways of tackling these through creating better social conditions for the most vulnerable communities. 'The conditions in which people live and work can help to create or destroy their health - lack of income, inappropriate housing, unsafe workplaces, and lack of access to health systems are some of the social determinants of health leading to inequalities within and between countries' (WHO, 2006). Social and environmental factors are at the root of much inequality relating to both communicable and non-communicable disease. The goals of the CSDH are to support health policy changes in countries by: assembling and promoting effective, evidence based models and practices; to support countries in placing health equity as a shared goal across governments and other sectors of society, and to build a sustainable global movement. 'A major thrust of the commission is turning public health knowledge into political action' (Marmot, 2005)

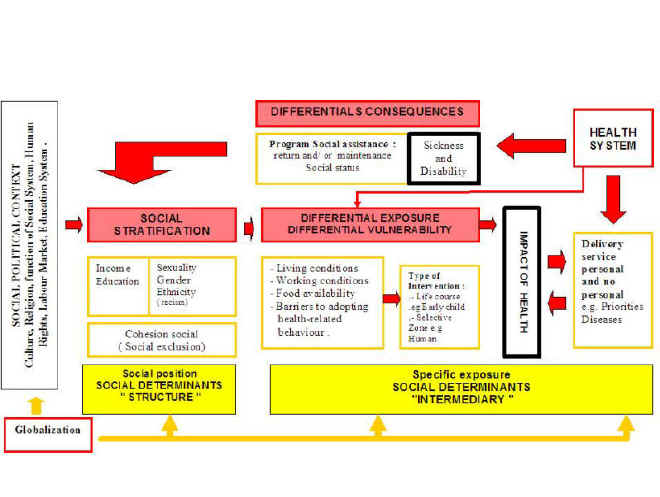

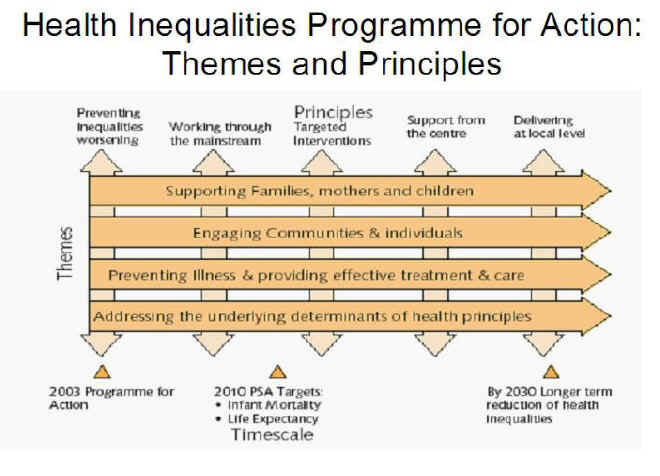

Fig. 1.2 shows the comprehensive framework proposed by CSDH that seeks to explain and illustrate the relationships between determinants and health, their causal role in generating health inequities, and the levels for policy action. Fig. 1.3 shows the model from the UK used to implement policy to tackle health inequalities, demonstrating the interrelationships between the themes and principles.

Fig 1.2 WHO Commission on Social Determinants & Health - Conceptual framework (2005)

Fig. 1.3 Tackling health inequalities - a programme for action (2003)

Exciting recent research has explored biological markers and physiological explanations for the effects on health of social determinants especially of prolonged chronic stress. Cell aging can be measured by the length of the telomeres, the structures at the end of the chromosomes that repair cell damage, and which shorten after each cell division. Psychological stress, both perceived and objectively measured stress levels, has been shown in women to be significantly associated with higher oxidative stress and shorter telomere length. Epel et al (2004) show that women with the highest levels of perceived stress have telomeres shorter on average by the equivalent of at least one decade of additional aging compared to low stress women. These findings have opened up a new area of interdisciplinary research that attempts to explain the causative factors and opportunities for intervening, across the 'interdisciplinary canyon' from cell biology to social and psychological studies (Sapolsky, 2004), which is fundamental to future public health action on health inequalities.

References

- Dahlgren G & Whitehead M (1991) Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Institute for Future Studies, Stockholm (Mimeo)

- Department of Health (2003) Tackling health inequalities. A Programme for Action. www.doh.gov.uk/healthinequalities/programmeforaction

- Epel ES, Blackburn EH, Lin J et al (2004). Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 17312-17315

- Marmot M (2005) Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet, 365: 1099-104

- Sapolsky RM (2004) Organismal stress and telomeric aging: an unexpected connection. www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/101/50/17323 accessed 3/10/06

- WHO (2006) Commission on Social Determinants of Health. www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/csdh_brochure.pdf

- Commission on Social Determinants (2006) Towards a conceptual framework for analysis and action on the social determinants of health. Draft discussion paper. www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/framework.pdf

- Wilkinson R & Marmot M (Eds.) (2003) Social determinants of health: the solid facts. 2nd Edn. Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- Selected key references on the evidence of the relationships between social factors and health drawn from The Solid Facts include:

- Barker DJP. Mothers, babies and disease in later life, 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Churchill Livingstone, 1998.

- Bethune A. Unemployment and mortality. In: Drever F, Whitehead M, eds. Health inequalities. London, H.M. Stationery Office, 1997.

- Framework Convention on Tobacco Control [web pages]. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2003 (http://www.who.int/gb/fctc/,

- Kawachi I et al. A prospective study of social networks in relation to total mortality and cardiovascular disease in men in the USA. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 1996, 50(3):245-251.

- Kawachi I, Berkman L, eds. Neighborhoods and health. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2003

- Mackenbach J, Bakker M, eds. Reducing inequalities in health: a European perspective. London, Routledge, 2002.

- Makela P, Valkonen T, Martelin T. Contribution of deaths related to alcohol use of socioeconomic variation in mortality: register based follow-up study. British Medical Journal 1997, 315:211-216

- Marmot MG et al. Contribution of job control and other risk factors to social variations in coronary heart disease incidence. Lancet, 1997, 350:235-239.

- Marmot MG et al. Contribution of job control to social gradient in coronary heart disease incidence. Lancet, 1997, 350:235-240.

- Marmot MG, Stansfeld SA. Stress and heart disease. London, BMJ Books, 2002.

- Marsh A, McKay S. Poor smokers. London, Policy Studies Institute, 1994.

- ODPM, Making the connections: transport and social exclusion. London, Social Exclusion Unit, Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, 2003 (

- Theorell T, Karasek R. The demand-control-support model and CVD.In:

- Schnall PL et al., eds. The workplace and cardiovascular disease. Occupational medicine. Philadelphia, Hanley and Belfus Inc., 2000: 78-83.

1.2 The Public Health Movement and health promotion

The changes in the structure and organisation of society, and in the knowledge of causes of disease over the last century or so, have shifted the focus of understanding and attention to different influences on health with concomitant effects on the resourcing and structure of health care. There have been three distinct phases in the public health movement, since the mid 19th century to the current time in western Europe, in relation to industrialisation and increasing access to health care and pharmaceuticals. Between the 1830's and 70's in England there was recognition of the need to take action on housing and sanitation, and the provision of safe water and adequate food. These environmental responses to preventing infectious disease and improving health were evident in the National Public Health Acts in 1846 and 1875 showing government taking responsibility through legislation for preventing disease in communities living in poverty. This was followed by an era of growing understanding of the transmission of disease - the germ theory - which increased the focus on individual approaches to prevention; including the introduction of immunisation and vaccination, and community and school health services to support mothers and children. The emphasis in these initiatives was more on providing information and some practical support to enable individuals to take responsibility for taking the actions necessary to keep themselves healthy.

The third discernible phase is the therapeutic era, from the 1930's to the 1970's, with the discovery of insulin and sulphonamide drugs, a time of expansion of hospital and treatment services and the sense that medicine was 'a magic bullet' that could cure all individual ills, regardless of the context of people's everyday lives. This was debunked principally by the analysis of Thomas McKeown who produced the background for a new public health based on the study of population growth and mortality. He concluded that the high death rates of the past, particularly in children, were attributable to a combination of infectious disease, nutrition and other environmental factors: 'in order of importance the major contribution to improvements in health in England & Wales were from limitation of family size (a behavioural change), increase in food supplies and a healthier physical environment (environmental influences) and specific preventive and therapeutic measures' (McKeown, 1976). Healthy public policy and its implementation is therefore characterised by consideration of all of the following themes:

-

Individual behaviour versus collective (social) responsibility for health

-

Action on the determinants of health, the environment, and poverty

-

The impact of high investment in health care facilities and treatment including pharmaceuticals

-

Role of government and legislation

1.3 The Lalonde Report & Health for All

In 1974, the Canadian Minister of Health, Marc Lalonde, published a government report on A new perspective on the health of Canadians, which focussed attention on the fact that much ill-health in Canada was preventable. This introduced a simple conceptual framework to organise the various factors that influence health, this was called the 'Health Field Concept' whose key elements are shown in Box 1.1:

|

Box 1.1 The Health Field Concept (Lalonde, 1974)

Lalonde M (1974) A new perspective on the health of Canadians, a working document. Ottawa, Government of Canada |

This report set the scene for a re-emergence of public health, and for health of the population being a legitimate concern and responsibility of governments. This was endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in the Declaration of Alma Ata on primary health care following the Thirtieth World Health Assembly in 1977 which resolved that: 'the main social target of governments and WHO in the coming decades should be the attainment by all citizens of the world by the year 2000 of a level of health that will permit them to lead a socially and economically productive life'. The Global Strategy of Health for all by the Year 2000 (HFA 2000) endorsed and developed the approaches necessary to achieve this goal. Its principles emphasised the importance of the development of primary health care, the need for real community participation, and the imperative of intersectoral collaboration between sectors and agencies. The main objectives were the promotion of lifestyles conducive to health, the prevention of preventable conditions and provision of rehabilitation and health services. This was further developed for the European Region in its HFA strategy (WHO, 1981) and clearly operationalized in the Targets for Health for All published in 1985 (WHO, 1985).

There were thirty-eight targets, grouped as follows:

-

Targets 1-12: Health for All; covering equity, increasing life expectancy and reducing disease

-

Targets 13-17: Lifestyles conducive to Health for All; (including Target 13 'Developing healthy public policies' detailed in Box 1.2)

-

Targets 18-25: Producing healthy environments; including environment, housing and work-related risks

-

Targets 26-31: Providing appropriate care; with a focus on primary care and the importance of improving quality of services

-

Targets 32-38: Support for health development; covering research, information, education & training and health technology assessment.

As can be seen from this brief listing, the targets are a holistic approach to health improvement, with actions in all sectors required. There is also a clear prediction of the requirement of advanced technologies in terms of evidence, education and quality improvement for example.

|

Box 1.2 HFA 2000 Target 13 Healthy Public Policy By 1990, national policies in all Member States should ensure that legislative, administrative, and economic mechanisms provide broad intersectoral support and resources for the promotion of healthy lifestyles and ensure effective participation at all levels of such policy-making. The attainment of this target could be significantly supported by strategic health planning at cabinet level, to cover broad intersectoral issues that affect lifestyle and health, the periodic assessment of existing policies in their relationship to health, and the establishment of effective machinery for public involvement in policy planning and development. WHO (1985) Targets for Health for All, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen |

1.4 Health promotion concepts and principles

There are three basic approaches (models) of health promotion which can be summarised as the medical/behavioural change, educational and social change models. In practice these models overlap but at their most separated can be described to show their differences as follows:

- The medical model is based on the prevention of disease (illness/'negative health') as an entity of the host individual with a focus on the biomedical model of health combined with a philosophy of compliance with professionals' diagnosis and prognosis - usually the doctor.

- The educational model is based on the view that the world consists of rational human beings and that to prevent disease and improve health you merely have to inform or educate people about the remedies and healthy lifestyles and as rational human beings they will respond accordingly.

- The social model is based on a view that health is determined by the social/cultural and physical environment and hence the solutions are more fundamental and political, and people need to be protected from health disabling environments.

These models may influence professionals perspective on health, illness and the causes of what makes people well or ill, which may further influence the treatment. For example, a professional strictly following the medical model, will determine hyperlipidaemia and hypertension as causes of heart disease, whereas a social epidemiologist may consider stress, poor living and working conditions as main contributory factors for heart disease.

Like all models these are simplifications of reality and as such are all incomplete, in practice health promotion is a combination of these approaches. Health promotion can be seen as part of the natural progression and extension of health education, which has embraced the lessons of the past concerning the need to combine the actions of individuals with those of society to achieve optimal health. The focus is on taking the best combination of actions to achieve the best possible health outcomes for the community and the individual. Identifying scientifically sound solutions to measurable health problems is the base on which such action is built.

On the other hand, health promotion may be seen as having more complex and radical roots, representing a reaction to the medically dominated, individually-focused health systems which evolved in the years following the second world war. In this context a wider set of goals which emphasise the achievement of equity, social justice, participation and self determination are seen as being the essential elements of health promotion.

Health promotion began to be seen as one of the key vehicles to implement the HFA 2000 strategy and healthy public policy. The principles and values of the practice of health promotion are embedded in HFA 2000. The WHO (1984) document on concepts and principles of health promotion, and the Ottawa Charter (1986) define the principles of health promotion as:

-

involving the population as a whole in the context of their everyday life, rather than focusing on people at risk for specific disease.

-

directed towards the action on the determinants or causes of health; requiring co-operation between sectors and government responsibility

-

combining diverse, but complementary, methods or approaches; including individual communication and education as well as legislation and fiscal measures, organisational and community development

-

effective and concrete community participation

-

involvement of health professionals, particularly in primary health care

The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion resulted from the first International Conference on Health Promotion that met in Ottawa in November 1986, and it has since provided an endurable vision and practical focus for the development of health promotion. Its definition of health promotion has been universally accepted as:

'…the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health'.

This is a salutogenic view of health (Antonovsky, 1996). The salutogenic perspective advocates strengthening people's health potential and recognising that good health is a means for a productive and enjoyable life. Human rights are fundamental to health promotion, as is a concern for equity, empowerment and engagement. In addition it has the following characteristics:

-

Health promotion is a process - a means to an end

-

Health promotion is enabling - done by, with and for people, not imposed upon them

-

Health promotion is directed towards improving control over the determinants of health

The Ottawa Charter called for action in five now familiar arenas:

-

building healthy public policy

-

creating supportive environments

-

strengthening community action

-

developing personal skills

-

reorienting health services.

The Ottawa Charter pledges (Box 1.3) were the global commitments made to take health promotion into the future.

|

Box 1.3 The Ottawa Charter pledges:s

Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, Health Promotion, 1:4, 1987 |

Since then WHO has played a leading role in health promotion throughout the world, both by sponsoring further international conferences to explore further practical experience with the major action strategies of the Ottawa Charter, and by promoting a "settings" based model for health promotion. Two WHO conferences which have extended our knowledge and understanding of the strategies defined in the Ottawa Charter were held in Adelaide, Australia to examine international experience in developing healthy public policy (WHO, 1988), and in Sundsvall, Sweden to explore ways and means of creating supportive environments for health (WHO, 1991). In the latter case WHO supported the development of the Healthy Cities Project, a network of Health Promoting Schools, and action to support the development of health promoting worksites and health promoting hospitals.

The charter principles have also been reviewed and updated in subsequent WHO conferences, in Jakarta (WHO, 1997), where there was a focus on creating partnerships between sectors, including private/public partnerships. The priorities for the twenty-first century were considered to be to:

-

Promote social responsibility for health

-

Increase investment in health development

-

Consolidate and expand partnerships for health

-

Increase community capacity and empower the individual

-

Secure an infrastructure for health promotion

These principles have also been reviewed in the 2005 WHO International conference on Health Promotion in Bangkok for a new charter for the 21st century that reflects the changes in globalisation and need for global governance for health. In practice the original five arenas for action: building healthy public policy; creating supportive environments; strengthening community action; developing personal skills; and reorienting health services are still considered to be the essential foundation stones of health promotion practice today.

References

- Antonovsky A (1996) The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promotion International, 11(1): 11-18

- Lalonde M (1974) A new perspective on the health of Canadians, a working document. Ottawa, Government of Canada

- McKeown T (1976) The role of medicine - dream, mirage or nemesis? Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust, London

- Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (1986) Health Promotion 1:4

- WHO (1981) Global Strategy for Health for All by the Year 2000. WHO, Geneva

- WHO (1984) Health Promotion: a discussion document on the concept and principles. WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen

- WHO (1985) Targets for health for all. WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen

- WHO (1988) The Adelaide Recommendations: Healthy Public Policy. WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen

- WHO (1991), Sundsvall statement on creating supportive environments for health. WHO, Geneva

- WHO (1997) The Jakarta declaration on leading health promotion into the 21st century. WHO, Geneva

- World Health Organization (2005) The Bangkok Charter for health promotion in a globalized world. www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/6gchp/bangkok_charter

For an overview of global health challenges and reviews of approaches taken in public health policy and health promotion from different parts of the world see also: Scriven A & Garman S (Eds.) (2005) Promoting health, global perspectives .Basingstoke, Palgrave MacMillan

© V Speller 2007