PLEASE NOTE:

We are currently in the process of updating this chapter and we appreciate your patience whilst this is being completed.

Concepts of health, wellbeing and illness, and the aetiology of illness: Section 11. Social capital and social epidemiology

This section covers:

1. The concept of social integration

2. Social capital

3. Social epidemiology

1. The concept of Social integration

Although the psychosocial concept of social support is clearly central to an understanding of the impact of social stresses upon health, it cannot account for the changes in social networks that have occurred in Western societies over the past century. For an explanation of these processes we have to look to sociological theory.

In his classical study of suicide written in 1899, Durkheim argued that an individual's integration into society is essential for their health and wellbeing. Modern societies are seen to be organised around individual differences (specialised division of labour) rather than upon their similarities. These societal developments were seen to encourage self-interest rather than ‘social solidarity'. Individuals learn to become less dependent on others and to recognise only their own private interests - the sociological concept of 'anomie'. In times of personal crisis, because we are less well integrated into social groups, we lack the social support required to cope with the stresses of modern life.

More recent sociological studies of mental health and illness have supported Durkheim’s original hypothesis. The family, religious practices, along with other ‘integrating institutions' such as work/employment, are recognised as binding individuals into wider social relationships and so offer a sense of belonging and meaning. This serves to protect individuals from the consequences of anomie by providing a sense of structure and social status. It follows that the events commonly associated with stresses within the family, unemployment (particularly among young men), etc, have a particularly important impact on health because they represent, "psycho-social transitions, and tend to reduce the ties that the individual experiencing them has with others ' (Stroebe and Stroebe:1995).

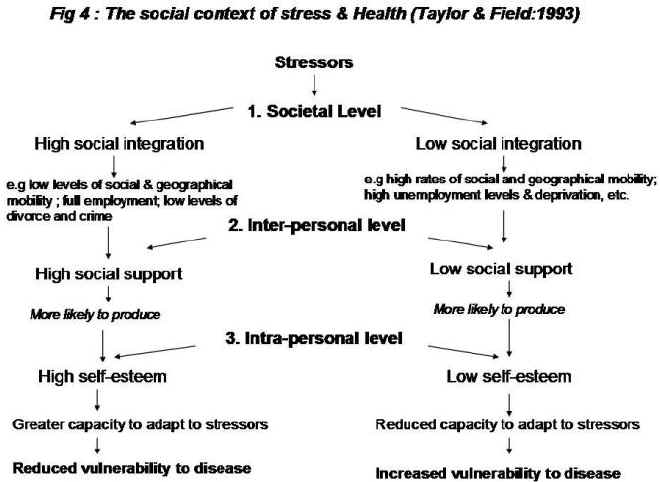

Whilst levels of social integration and social support are related, the former is a characteristic of populations or institutions, whilst the latter is a property of individuals. The relationship between these two concepts as psycho-social mediators of social stress and its impact upon health is diagrammatically represented in Figure 8 below.

Figure 8: The social context of stress and health (Taylor & Field, 1993).

See Glossary for Section 11

2. Social capital

Social capital is the value attributed to social networks, defined by Woolcock (1998) as ‘the norms and networks that facilitate collective action’. This definition is similar to that of Putnam et al. (1993), and is reflected in the World Bank (2011) definition: ‘Social capital is not just the sum of the institutions which underpin a society – it is the glue that holds them together’. Social capital is a function of social integration, and is enhanced through bonding within social networks, and bridging between networks. It operates at the micro, meso and macro levels: the micro and meso levels refer to interactions between individuals and their immediate families or communities, and the macro level refers to interactions at a national level, including political and cultural institutions.

Norms refer to acceptable boundaries within networks, and can be formal (e.g. legislation or voluntary policies) or informal (i.e. the unwritten and often unspoken conventions that govern behaviour or social practice). Consequently sanctions, which happen when these boundaries are crossed, may be imposed formally or legally, e.g. through fines or imprisonment, or socially, e.g. through stigma or social exclusion. They may also be internalised, i.e. imposed through our own expectations rather than by the actions of others. Norms and sanctions reflect the values or culture of networks – for example, a culture that values material possessions will have strong norms around respect for others’ property, and strong sanctions against theft or vandalism.

The relationship between norms and sanctions, and in turn their relationship to social capital and exclusion, is not always straightforward. Strong or weak enforcement of sanctions affects the extent to which norms are upheld; for example, people may be more likely to evade fares on public transport if they know there is unlikely to be a ticket inspection or barrier. Alternatively, the perceived benefit of going against a norm may outweigh any sanctions, or even be a desirable pursuit in itself – for example, tattoos and piercings contravene social norms of appearance in Western and many other societies, but are considered an important form of self-expression for those who choose to have them (e.g. Milner & Eichold, 2001). In addition, the increasing prevalence of body modifications, particularly among younger people, may reflect a shifting of norms. The reduction in smoking prevalence in the UK following a ban in smoking in public places is a recent example of how norms can be shifted quite quickly, even when they appear to be entrenched in a population.

Portes (1998) makes the distinction between sources and effects of social capital. Sources of social capital are the characteristics of networks, i.e. the motivations to make resources available, and its effects are the actual resources provided (e.g. social support or opportunities). Motivations may include internalised norms or morals, solidarity or empathy with others, or expectations of repayment (reciprocity norms). An obvious problem with norms as a basis for providing social capital is with how these norms are established, and their differential impacts depending on the balance of power; what bonds one set of people together may exclude or isolate another. The WHO (2008) emphasises the relationship between human rights and social inclusion, recommending that action should be taken to promote human rights as a means to reverse social exclusion and enhance social cohesion. The WHO also advises that the term ‘social exclusion’ should only be used when more specific descriptors (e.g. racism or food insecurity) are not available.

Social capital is recognised as being positively associated with a number of health and social outcomes at all levels, but again the relationship is complex. A study by the WHO’s Regional Office for Europe found that individual social capital was only effective if there was also social capital at the community level, and that community social capital alters the reporting of individual social capital (Rocco & Suhrcke, 2012).

Asset-based community development

Social capital is central to the concept of asset-based community development (ABCD).[1] ABCD is an approach that views citizens as active participants rather than passive recipients (i.e. doing ‘with’ instead of doing ‘to’). Instead of the traditional deficit-centred approach to solving problems, it focuses on mobilising individual and community assets and maximising existing resources to improve population health and wellbeing. The five key assets in ABCD are individuals, associations, institutions, physical assets, and connectors. Individuals, or residents of a community, are at the heart of ABCD, and may come together to form associations that help to mobilise their communities. The aim of ABCD is to provide people with the tools they need to make positive changes in their lives, and to create environments that are conducive to change. It is also consistent with a patient-centred approach to healthcare, which advocates giving patients the information they need to make shared decisions with their clinicians (see Section 2).

3. Social epidemiology

Social epidemiology is the study of socio-structural effects on health, based on the assumption that the distribution of advantages and disadvantages in a society reflect the distribution of health and disease (see Honjo, 2004; Krieger, 2001). While this relationship has been researched extensively throughout the 20th century, the application of contemporary epidemiological methods is a relatively new development. Social epidemiology aims to determine the extent to which health is influenced by micro-, meso- and macro-level characteristics. It does this through measuring and monitoring health inequalities (surveillance), investigating the social causes of illness, and designing and evaluating interventions to reduce health inequalities.

© I Crinson 2007, Lina Martino 2017