Principles underlying the development of clinical guidelines, clinical effectiveness and quality standards, and their application in health and social care

Defining and measuring quality

Definition

In order to assess and improve health and social service quality, it is first necessary to define ‘quality’. The World Health Organisation (WHO) states that quality healthcare is that which is effective, efficient, accessible, acceptable, equitable and safe[i].

Figure A: WHO healthcare quality dimensions, adapted from Quality of Care, (WHO, 2006)[i

|

WHO healthcare quality dimensions

|

The English National Health Service (NHS) Constitution includes as one of its key principles ‘the highest standards of excellence and professionalism [including] high quality care’, which it defines as ‘care that is safe, effective and focused on patient experience’.[ii]

As part of the NHS Five Year Forward View, the National Quality Board was set up, consisting of the six partner organisations who developed the Forward View - the Care Quality Commission (CQC), NHS England, NHS Improvement, Public Health England (PHE), the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and Health Education England (HEE), with the Department of Health (DH) as the overall ‘system steward’[iii],[iv]. The Board have since published a Shared Commitment to Quality, which provides separate definitions of quality for those using and those providing services, supplementing the original NHS definition of safety, effectiveness and positive experience with the additional dimensions of collaboration; efficiency and equity[v].

Figure B: NHS England healthcare quality dimensions, adapted from NHS Shared Commitment to Quality (NHS, 2016)[iv]

|

NHS England healthcare quality dimensions for those who use services |

NHS England healthcare quality dimensions for those who provide services |

|

Safety: People are protected from avoidable harm and abuse and lessons are learned when mistake occur. |

Transparent, collaborative and reflective: Services are transparent, collaborate internally and externally and are committed to learning and improvement. |

|

Effectiveness: People’s care and treatment achieves good outcomes, promotes a good quality of life, and is based on the best available evidence. |

Efficient: Services use their resources responsibly and efficiently, providing fair access to all, according to need, and promote an open and fair culture. |

|

Positive experience (caring, responsive and person-centred): Staff involve and treat people with compassion, dignity and respect and services respond to people’s needs and choices and enable them to be equal partners in their care. |

Equitable: Services ensure inequalities in health outcomes are a focus for quality improvement, making sure care quality does not vary due to a persons characteristics, as protected under the Equality Act 2010. |

Measurement

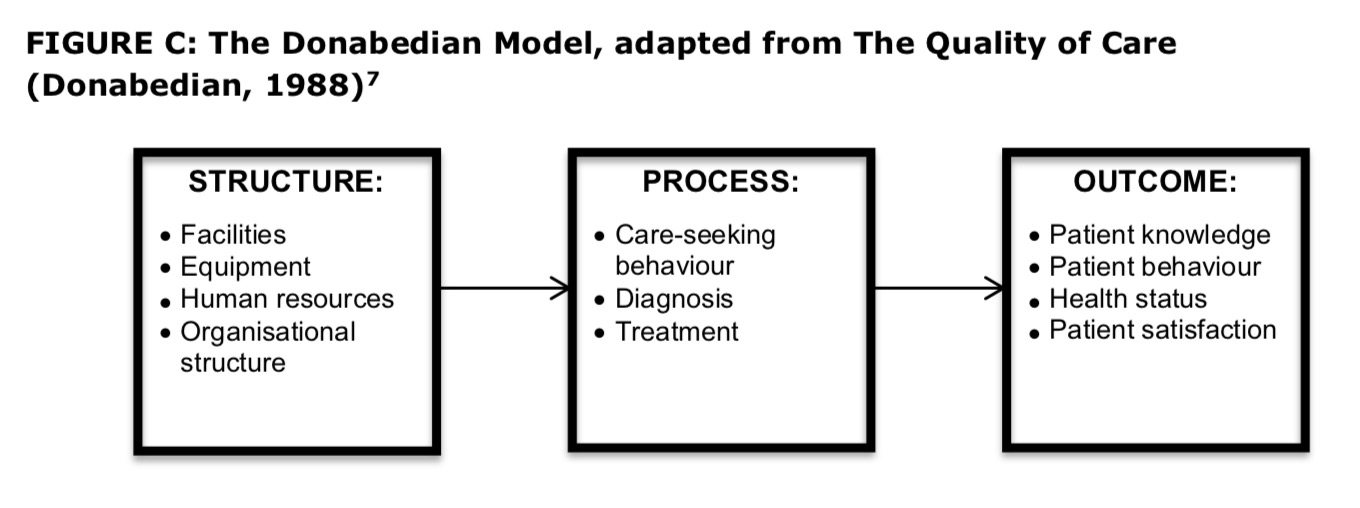

In moving from definition to measurement, it is necessary to consider which components of care will be accessed for quality. The Donabedian model is commonly cited as the basic model for assessing, and thereby improving, health care quality. It considers the measurement and improvement of quality in three key stages of health care - the structure, or environment in which health care is provided; the process, or method by which health care is provided; and the outcome or result that is achieved as a result of the health care[vi]. Donabedian reflected on the advantages and disadvantages of measuring quality at each stage of the health care process, and concluded that ‘As a general rule, it is best to include in any system of assessment, elements of structure, process and outcome [as] this allows supplementation of weakness in one approach by strength in another’[vii].

FIGURE C: The Donabedian Model, adapted from The Quality of Care (Donabedian, 1988)[vii]

The Kings Fund Report ‘Getting the measure of quality: Opportunities and challenges’ (2010) provides an overview of the practicalities of choosing and using different types of indicators for the measurement of quality[viii].

Clinical guidelines and quality standards

Developing guidelines and standards

Clinical guidelines recommend how health and social care professional should care for people with specific health conditions and can include recommendations about providing information and advice as well as prevention, diagnosis, treatment and longer-term management[ix]. Quality standards describe priority areas for quality improvement in a defined area of health or social care, and include both ‘quality statements’ that are aspirational but achievable as well as ‘quality measures’ that can be used to assess the quality of care or service provision specified in the statement[x]. Quality standards enable practitioners to make decisions based on the latest evidence and best practice; allow commissioners to be confident that they are purchasing high quality and cost effective services; enable services providers and users to know what quality of service they should expect to provide or receive; and allow benchmarking against other services[xi].

In England an independent public body - the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) - provides national guidelines and sets quality standards in order to improve health and social care quality. Topics for the development of new guidelines are prioritised based on the priorities of commissioners, professional organisations, service users and their families and carers.

NICE also receives requests for the creation of new quality standards from other government organisations such as NHS England, the Department of Health and the Department of Education.

NICE guidelines are developed in accordance with internationally recognised guideline development methodology as detailed in the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II)[xii]. Similar methodology is used by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) to produce guidelines for NHS Scotland[xiii] and NICE has also produced a separate guide to support the development of clinical quality standards in low and middle-income countries[xiv]. Both NICE and SIGN use the international GRADE system to grade the quality of evidence prior to making recommendations via guidelines or quality statements. The GRADE system classifies evidence as being of high quality, moderate quality, low quality, or very low quality, as shown in Figure D, below[xv],[xvi].

Figure D: GRADE Quality of evidence definitions, adapted from GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations (BMJ, 2008)

|

Figure E, below, outlines the key principles for the development of NICE guidelines and quality standards, with further details available in the relevant NICE publications[xvii],[xviii].

Figure E: Principles of guideline and quality standard development, adapted from Developing NICE Guidelines: The Manual (NICE, 2014) and Quality Standards: Process Guide (NICE, 2014)

|

Key principles for developing NICE guidelines

Key principles for developing NICE quality standards

|

Implementing guidelines and standards

It is important to recognise that the development of good guidelines does not automatically ensure their use in practice. The multiple factors that influence healthcare professionals‘ behaviour must be taken into consideration, and it is recommended that in order to maximise the likelihood of guidelines being used there is a need for coherent dissemination and implementation strategies that deal with any obstacles to implementation that have already been identified[xix].

Furthermore, while guidelines are developed and implemented with the aim of improving healthcare quality, the limitations and potential harms of guidelines must also be considered. It is important to remember that clinical guidelines are only one option for improving the quality of care, and that while their development and implementation is appropriate in cases where lack of knowledge is the cause of poor quality, they will do little to help to address poor quality care that is the result of non-knowledge based factors[xx].

© Flora Ogilvie 2017

[i] WHO. Quality of Care: A process for making strategic choices in health systems. 2006. http://www.who.int/management/quality/assurance/QualityCare_B.Def.pdf

[ii] NHS. The NHS Constitution for England. 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/480482/NHS_Constitution_WEB.pdf

[iii] NHS. NHS Five Year Forward View. 2014. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf

[iv] NHS Quality Board. 2014. https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/part-rel/nqb/

[v] NHS. Shared Commitment to Quality. 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/nqb-shared-commitment-frmwrk.pdf

[vi] Visnjic A, Velickovic V, Jovic S. Measures for improving the quality of health care. Scientific Journal of the Faculty of Medicine in Nis 2012; 29(2): 53-58.

[vii] Donabedian A. The quality of care: how can it be assessed? JAMA 1988; 260(12): 1743-1748.

[viii] Raleigh V and Foot C. Getting the measure of quality: Opportunities and challenges. The Kings Fund. 2010. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/Getting-the-measure-of-quality-Veena-Raleigh-Catherine-Foot-The-Kings-Fund-January-2010.pdf

[ix] NICE. Types of guideline.

https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/nice-guidance/n…

[x] NICE. Quality standards: Process guide. 2014.

http://www.nice.org.uk/media/default/Standards-and-indicators/Quality-s…

[xi] NICE. Standards and indicators.

[xii] Appraisal of guidelines, research and Evaluation. http://www.agreetrust.org

[xiii] SIGN. Methodological Principles. http://www.sign.ac.uk/methodology/index.html

[xiv] NICE International. Principles for developing clinical Quality Standards in low and middle income countries: A Guide, Version 2. June 2015

http://www.idsihealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/QS-process-Guide-2…

[xv] GRADE. From evidence to recommendations. http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org

[xvi] Guyatt G et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations BMJ 2008; 336 :924

[xvii] NICE. Developing NICE guidelines: The manual. 2014

https://www.nice.org.uk/article/PMG20/chapter/1Introductionandoverview

[xviii] NICE. Quality standards: Process guide. 2014.

http://www.nice.org.uk/media/default/Standards-and-indicators/Quality-s…

[xix] Feder G et al. Using clinical guidelines BMJ 1999; 318 :728

[xx] Woolf S et al. Potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines BMJ 1999; 318 :527