Personal management skills (e.g. Managing: time, stress, difficult people, meetings)

Understanding Individuals: Personal Management Skills

This section covers:

- Personal management skills

- The effective manager

To be an effective manager, an individual needs to be able to manage themselves as well as knowing how to manage others

Personal management skills

Stress and time management are both key to effective management of oneself. The time management matrix is a useful tool to allow prioritisation of individual workload:

|

|

Urgent |

Not urgent |

|

Important |

1 |

2 |

|

Urgent & Important |

Not urgent but Important |

|

|

Not important |

3 |

4 |

|

Urgent but not important |

Not urgent & not important |

Quadrant 1 relates to things that are important and need to be done there and now, while quadrant 2 relates to important things which need strategic planning and development in the long term, but are often given little consideration. Essentially where time is short, important things in these two quadrants should be prioritised.

Quadrant 3 covers those things that are often prioritised because of their urgency even if they are not important, while quadrant 4 relates to those things that do not really need doing.

Good time management can help reduce stress, but the following also help with the latter:

- Being aware of and recognising the symptoms of stress in oneself and others

- Understanding the causative factors

- Applying means to prevent, avoid and reduce stress

The effective manager

'In contemporary health services, there is undoubtedly a great deal of pressure on those in management positions. This pressure comes mainly from having to cope with considerable changes both internally and in the external environment. These changes are to do with the consumers of the services; with the changing demands of the professionals who operate the services as well as central policy and significant structural changes.' (Stewart, 'Leading in the NHS : A Practical Guide')

The aim of this Section is to introduce the concept of management in the health and social care professions in the context of today's fast-changing health and social care environments, present various concepts and theories designed to help you understand, clarify and explain issues in your own work situation and those of others.

Before we proceed to explore some of the key literature on managers and management it is worth considering how the environments in which managers operate have changed over the last 5 -10 years or so.

|

Past |

Present |

|

Centralised Hierarchies |

Semi-autonomous Work Units |

|

Power Vested in Management |

Empowerment of All |

|

Distrust |

Trust |

|

Quantitative Productivity |

Intuition, Innovation and Creativity |

|

Planning for Patients |

Planning with Patients |

It is important to look at principles of leadership and delegation to consider the differences and overlaps between management and leadership.

Definitions

Collins Concise Dictionary defines a 'manager' as 'a person who directs or manages an organisation, industry, shop ……'

But this is hardly sufficient for our purpose. We need greater depth and detail.

In management books the manager's task has traditionally been expressed as 'maximising the use of resources to meet the aims and objectives of the organisation in the light of the (competing) environment that it operates in.'

A more detailed traditional text-book view of managers and the work they perform would probably read something like this:

A manager is the person responsible for planning and directing the work of a group of individuals, monitoring their work, and taking corrective action when necessary. Managers may direct workers directly or they may direct several other managers and/or supervisors who direct the workers. The manager must be familiar with the work of all the groups he/she supervises, but does not need to be the best in any or all of the areas. It is more important for the manager to know how to manage the workers than to know how to do their work well.

But the recent transition toward high performance customer/consumer/patient focused work teams and the introduction of multi-agency partnerships is resulting in significant changes to the manager's role. Today's managers must be able to adapt to change; provide vision, principles, and boundary conditions, align people toward a purpose; set direction and strategy. As teams and partnership-working take on more and more responsibility, the manager's focus shifts from controlling and problem solving to motivating and inspiring.

For a wider view on managers and management let's look at what management gurus Peter Drucker and Charles Handy have to say:

Drucker tells us:

'Management means, in the last analysis, the substitution of thought for brawn and muscle, of knowledge for folkways and superstition, and of cooperation for force. It means the substitution of responsibility for obedience to rank, and of authority of performance for the authority of rank.'

A modern manager, he tells us, 'is responsible for the application and performance of knowledge.'

Charles Handy in the 1999 edition of his 1976 classic 'Understanding Organisations' has a whole chapter - 'On being a Manager' - on the subject.

Interestingly Handy likens managers to General Practitioners (GPs) in that he/she is the 'first recipient' of a problem and must first of all decide whether it is a problem and, if so, what sort of problem it is. Managers/GPs alike need to follow the undernoted process as they search for solutions:

- Identify the symptoms

- Diagnose the disease (cause of the problem)

- Decide how it might be dealt with - 'strategies for health'

- Start the treatment (problem resolution)

Like GPs, managers may need expert assistance, or a second opinion at any of the above stages, but, as Handy points out, responsibility for each of these stages lies with the local GP/manager.

However, continuing the GP/manager analogy, problems can occur, writes Handy, when:

- the symptoms rather than the disease itself are treated

- the prescription is the same whatever the disease

The essential thing, says Handy, is for the GP/manager to make the correct diagnosis. Thus the skill of the GP and manager is to correctly assess and interpret information, symptoms and, using specialist inputs where necessary make the correct diagnosis, then take the right decisions, take the right courses of action to remedy the problem.

Problem Solving/Options Appraisal/Good Decision-making

Problem solving and options appraisal are two key requirements of all public health professionals. These skills are required for day-to-day decision making e.g. use of resources, as well as implementation of key government policies e.g. National Service Frameworks (NSFs) and NICE Guidelines.

Simon (The New Science of Management Decision, 1960) has shown that solution of any 'decision problem' in business, science or art can be viewed and handled in four steps:

1. Perception of decision need or opportunity. The 'intelligence' phase

2. Formulation of alternative courses of action

3. Evaluation of the alternatives for their respective contribution

4. Choice of one or more alternatives for implementation

Managers need to be able to understand the above sequence and be able to follow it in the context of their own work/workplace so as to be able to identify and deal with problems, make effective decisions.

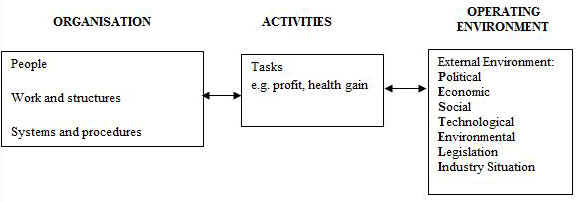

Management in Context

Each organisation is of course different and there will be key variables that have to be considered to determine the type of management that is required:

Four Key Management Activities

There are four key activities that a manager must achieve if he/she is to be successful in achieving key organisational objectives:

|

1. Plan |

P |

|

2. Organise |

O |

|

3. Motivate |

M |

|

4. Control |

C |

The 'POMC' approach:

- relies on activities where result outcomes are paramount to successful work programmes

- is more than just being leader i.e. counsellor/intermediary, catalyst/facilitator, diagnostician/engineer, many of these roles are important in public health function.

The POMC approach was derived from Henri Fayol and his Five Functions of Management as long ago as 1916. Fayol linked strategy and organisational theory, emphasising the need for management development and qualities of leadership. Fayol's 5 key elements of fundamentally industrial management remain the foundation stones on which all later gurus have built.

|

Fayol: Five Functions of Management |

Additional information required |

|

Forecast and Plan |

Set clear vision SMART objectives (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Time-bound) |

|

Organise |

Building up the structure:

|

|

Command |

Maintaining activity among the personnel:

|

|

Co-ordinate |

Unifying and harmonising all activity and effort:

|

|

Control |

Everything occurs in conformity with established rule and expressed command i.e. everything |

But Mintzberg's 'Nature of Managerial Work' (1973) which follows the overall POCM approach shows the realities of the 2nd-half of the 20th century to be very different:

Plan: (This has become and remains one of the classic approaches to organisational planning)

- where are we now? (current analysis of current situation)

- where do we want to be in a specified period of time? (vision, goals and objectives)

- how do we get there? (how do we organise our resources, motivate and manage our people)

- how do we know how successful we are? (how are we performing in regular reviews against 'critical success factors' and 'key performance indicators' : see 'Control' below).

This planning stage needs to consider organisational culture and any external influences that will affect the planning and implementation process. For example, the use of a PESTELI analysis.

Organise - resources: the '4 M's'

- manpower (workforce)

- materials

- machines

- money

Also: organisational structure, delegation and span of control, plus organisational development, formal communication in organisations, and time management.

Motivation -

is the ability of the manager to get his/ her subordinates' commitment to organisational goals.

Control -

There need to be regular and rigorous scheduled reviews of performance against Plan:

Mintzberg The Managerial Roles

Mintzberg groups managerial activities and ten associated roles as follows:

|

Managerial activities |

Associated roles |

|

interpersonal relationships - arising from formal authority and status and supporting the information and decision -making activities. |

|

|

information processing |

|

|

making significant decisions |

|

The broad proposition is that, as a senior manager enacts his/her role, these will come together as a gestalt (integrated whole) reflecting the manager's competencies associated with the roles. In a sense therefore they act as evaluation criteria for assessing the performance of a manager in his/her role.

Here we look at each of the roles in more detail:

1. Figurehead.

Social, inspirational, legal and ceremonial duties must be carried out. The manager is a symbol and must be on-hand for people/agencies that will only deal with him/her because of status and authority.

2. Liaison

This is the manager as an information and communication centre. It is vital to build up favours. Good networking skills are needed to shape and maintain internal and external contacts for information exchange are essential. These contacts give access to "databases" - facts, requirements, probabilities.

3. The Leader role

This is at the heart of the manager-subordinate relationship and managerial power and pervasive where subordinates are involved even where perhaps the relationship is not directly interpersonal. The manager:

- defines the structures and environments within which subordinates work and are motivated.

- oversees and questions activities to keep them alert.

- selects, encourages, promotes and disciplines.

- tries to balance subordinate and organisational needs for efficient operations.

4. Manager as 'monitor'

- the manager seeks/receives information from many sources to evaluate the organisation's performance, well-being and overall situation. Monitoring of internal operations, external events, ideas, trends, analysis and pressures is vital. Information to detect changes, problems and opportunities and to construct decision-making scenarios can be current/historic, tangible (hard) or soft, documented or non-documented. This role is about building and using an intelligence system. The manager must install and maintain this information system; by building contacts and training staff to deliver "information".

5. Manager as Disseminator

- the manager brings external views into his/her organisation and facilitates internal information flows between subordinates (factual or value-based).

The preferences of significant people are received and assimilated. The manager interprets/disseminates information to subordinates e.g. policies, rules, regulations. Values are also disseminated via conversations laced with imperatives and signs/icons about what is regarded as important or what 'we believe in'.

There is a dilemma of delegation. Only the manager has the data for many decisions and often in the wrong form (e.g. verbal/memory vs. paper). Sharing is time-consuming and difficult. He/she and staff may be already overloaded. Communication consumes time. The adage 'if you want to get things done, it is best to do it yourself' comes to mind.

Why might this be a driver of managerial behaviour (reluctance or constraints on the ability to delegate)?

6. Manager as Spokesman (e.g. in a 'P.R.' capacity)

- the manager informs and lobbies others (external to his/her own organisational group). Key influencers and stakeholders are kept informed of performances, plans and policies. For outsiders, the manager is regarded as an informed resource in the field in which his/her organisation operates.

7. Manager as Initiator/Changer

- a senior manager is responsible for his/her organisation's strategy-making system - generating and linking important decisions. He/she has the authority, information and capacity for control and integration over important decisions.

- he/she designs and initiates much of the controlled change and implementation in the organisation. Gaps are identified, improvement programmes defined. The manager initiates a series of related decisions/activities to achieve actual improvement. Improvement projects may be involved at various levels. The manager can:

1. delegate all design responsibility selecting and even replacing subordinates.

2. empower subordinates with responsibility for the design of the improvement programme but e.g. define the parameters/limits and veto or give the go-ahead on options.

3. supervise design directly.

Senior managers may have many projects at various development stages (emergent/dormant/nearly-ready) working on each periodically interspersed by waiting periods for information feedback or progress etc.

8. Manager as Disturbance Handler

- is a generalist role i.e. taking charge when the organisation hits a crisis or obstacle, perhaps unexpectedly, and where there is no clear programmed response. Disturbances may arise from staff, resources, stakeholders, external threats others make mistakes or innovation has unexpected consequences. The role involves stepping in to calm matters, evaluate, re-allocate, support - perhaps gaining some time.

9. Manager as Resource Allocator

- the manager oversees the allocation of resources (money, staff, premises, brand etc.). This involves:

1. scheduling his/her own time

2. programming work for self and others

3. authorising actions

The effective manager sets organisational priorities because time and access involve what are called 'opportunity costs'.

The managerial task is to ensure the basic work system is in place and to programme staff schedules - what to do, by whom, what processing structures will be used.

Authorising major decisions before implementation is a form of control over resource allocation. This enables coordinated interventions e.g. authorisation within a policy or budgeting process in comparison to ad-hoc interventions.

To help evaluation processes, managers often develop models and plans in their heads; these models/constructions encompass rules, criteria and preferences to evaluate proposals against. Loose, flexible and implicit plans are then regularly updated with new information as it is obtained/discovered.

10. Manager as Negotiator

- the manager takes charge over important negotiating activities with other departments, with management and with other organisations. The spokesman, figurehead and resource allocator roles demand this.

Comment

Mintzberg's ten roles point to managers needing to be both organisational generalists and specialists because of:

- system imperfections and environmental pressures.

- their formal authority is needed even for certain basic routines.

- in all of this they are still fallible and human.

The ten roles offer a wider and richer assessment of managerial tasks than the leadership models of, say, Blake or Hersey-Blanchard which explain, justify/legitimise managerial purposes (via contingency theory) in terms of:

1. designing and maintaining stable and reliable systems for efficient operations in a changing environment.

2. ensuring that the organisation satisfies those that own/control it.

3. boundary management = maintaining information links between the organisation and players in the environment.

References

Drucker P. 1977 'People and Performance'. Heinemann Books.

Handy C. 1976 (1999 edition) 'Understanding Organisations'. Penguin Books.

Rosemary, S. 1996. 'Leadership' in Leading in the N.H.S: A Practical Guide 2nd edition MacMillan Business, Chapter one pp.3- 13.

Further Support for Management Development

There are a number of UK organisations helping managers learn, develop and improve necessary skills and attributes.

- Learndirect has over 1,000 centres nationwide offering courses covering all areas of business, including 28 on Management Development.

Call the Learndirect Helpline on 0800 101 901 or visit http://www.learndirect.co.uk/

- The Association of Business Schools (ABS) represents leading business schools of UK universities, higher education institutions and independent management colleges. ABS promotes business and management skills to help improve the quality and effectiveness of UK managers.

- The Institute of Management is a professional body for managers in the UK. It aims to promote and provide management development for UK businesses.

- The Council for Excellence in Management & Leadership (CEML) is currently piloting the Business Improvement Tool for Entrepreneurs (BITE) with entrepreneurs and business professionals. The tool helps entrepreneurs identify development needs and provides sign-posting to a range of solutions that mimic the informal development opportunities which many entrepreneurs experience. (Source Department of Trade and Industry)

Management Models and Theories

Here is a summary of various relevant management models and theories that are covered more fully in Management Models and Theories:

|

Classical Theory |

|

|

Henri Fayol (1841 - 1925), France |

Practical manager (except Weber, sociologist) |

|

F W Taylor (1856 - 1915), USA |

Emphasis on structure |

|

Max Weber (1864 - 1924), Germany |

Prescriptive about 'what is good for organisations' |

|

Human Relations |

|

|

Elton Mayo and others (Hawthorne Studies) |

Academic, social scientists |

|

|

Emphasis on human behaviour within organisations |

|

|

People's needs are decisive factor in achieving organisations: effectiveness |

|

|

Descriptive and attempting to be predictive of behaviour within organisations |

|

Neo-Human Relations School |

|

|

Maslow |

Social psychologists

|

|

System Theories |

|

|

Tavistock Institute of Human Relations |

Organisations are complex systems of People, Task, Technology |

|

Technological environmental factors just as important as social/psychological |

|

|

Organisation - 'open system' with environment |

|

|

Contingency Theories |

|

|

Pugh (UK) |

Comprehensive view of people in organisations |

|

Burns and Stalker (UK) Lawrence/ Lorsch (USA) |

Diagnosis of People/Task/Technology/Environment - then suggest solutions |

© K Enock 2006, N Leigh-Hunt 2016